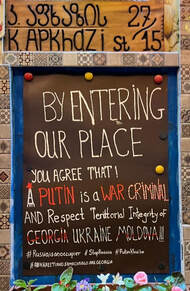

You'll note the question mark in the title of this missive. The idea of Europe—just what it is, and what it is not—is one of history’s great debates. You would think, as the Convocation of Episcopal Churches in Europe, we would have a crisp, clean idea of just what that means; but like so many other things in our church, when it comes down to cases, the answer sometimes is—it depends. I have just made my first visit to the easternmost outpost of the Convocation, the mission church of Saint Nino in Tbilisi, Georgia. (More about Saint Nino later.) The Republic of Georgia is a small land with an immense and complex history, stretching back thousands of years; archeologists have identfied evidence of viniculture stretching back as far as six millennia before Christ. What is now Georgia was once three kingdoms all part of Byzantine Empire, the eastern part of the Roman Empire; but that fractious fact made the country easy prey for expansionist Muslim forces as early as the seventh century C.E.  Once part of the Soviet Union, Georgia's recent history has in some ways been a preview of what is now happening in Ukraine. Putin's Russia fomented separatist movements in two regions of the country, Abkhazia and South Ossetia; this led to war in 2008 and subsequent occupation by Russia of the two regions. (It now appears that was merely a rehearsal for the drama we see unfolding today to the north across the Black Sea.) For the fourteen years since, twenty percent of Georgia has been effectively occupied by Russia—an outrage largely forgotten in the West. Needless to say, in Tbilisi there is prominent evidence of sympathy for the Ukrainian cause. Since the re-establishment of Georgia’s independence following the collapse of the Soviet Union (a process that was, unhappily, marked by civil strife), the Church has had a concordat with the state under which its unique place in the nation’s history is acknowledged. The Georgian Orthodox Church is not an established church, in the strict sense; but it is given tremendous influence over religious affairs in the country, and considerable indirect support from the government.  One of the ways that support is expressed is in the burdens placed on minority religions in organizing themselves. Our mission church has encountered tremendous challenges simply in obtaining the status of formal registration—and we have been advised that, once secured, something like 20 percent of all the funds held in the bank by the mission will be demanded by the government each year. It’s not hard to imagine that at least part of these funds might be diverted to help support what must be the enormous running costs of the Patriarchate’s gargantuan cathedral in Tbilisi , begun in 1995 and consecrated in 2004—and built, at least in part, over what had been an Armenian Orthodox cemetery attached to a church of that tradition destroyed during the Soviet era. Of such things deep enmity is made. The mission congregation is led by Thoma Lipartiani, a man in his early twenties with deep natural gifts for both the study of comparative religion and—more importantly—gathering into faithful community the marginalized, scorned, and disillusioned. He lives in a small apartment that during lockdowns became a house church; while I was there, he divided the community in half and hosted two separate receptions in his flat so that I could meet everyone (English-speakers the first night, Georgian-speakers the second evening). As i met them and listened to their stories, I gained a deeper sense of what has attracted people from a culture very unlike our own to a church so shaped by Anglo and American ideas. True, the fact that the Episcopal Church has affirmed a full place in the life and ministry of the church for LGBTQ+ people has attracted many to this community; but that by itself cannot be the organizing principle for a community of faith. Instead, what became clear to me is that this community of people responds deeply to the contrast between two different ideas of what should constitute the fundamental guideline of a Christian community—right belief (ortho doxy ) or right practice (ortho praxis ). The central idea of the “Way of Love” —and the discipline of walking along it (which is, itself, a matter of practice-led faith)—resonates far more deeply with a community of people who find themselves excluded by the stark lines drawn by teachings of right belief that stand above question or examination. Interestingly, perhaps, as I’ve been writing this reflection I’ve also been reading a recent blog post by Professor Scott MacDougall , theologian to the House of Deputies of the Episcopal Church, who has offered to those headed to General Convention this helpful yardstick for evaluating the various resolutions that will be taken up for consideration there: “...ask how each piece of legislation, if enacted, would either enhance or inhibit the ability of the Episcopal Church, in its wholeness or in its parts, to be the body of Christ in and for the world that church is called to be.” That emphasis on what we are supposed to be—and not quite so much on what we are expected to believe—is expressive of a focus on orthopraxis. Of course a church guided by orthopraxis must always—at least if it is wise—live comfortably together with the discipline of humility. It must always be holding up its practice against a set of core teachings, lest it simply become the instrument of the most popular, or seemingly most “effective,” messages. For those of us who live in this church in places where it is part of the dominant culture that discipline can be hard to remember, let alone exercise. But for our congregation in Tbilisi, that discipline comes almost as second nature.  On Sunday, we were—much to my astonishment—welcomed into the Roman Catholic co-cathedral of the Assumption of the Holy Virgin, where I had the privilege of confirming two members of the church and receiving fourteen—not fewer than three of whom are named “Nino.” Don’t be misled by that last vowel—Georgian isn’t a Latin language, and Nino was a woman, the “Equal of the Apostles and Enlightener of Georgia.” A fourth-century nun from Armenia, she played a pivotal role in spreading the Christian message among the rulers of Georgia. Many women in Georgia are still named for her. Even more astonishing to me was the presence of our host, Bishop Giuseppe Pasotto the Roman Catholic bishop of Tbilisi, for the entire service. He warmly greeted us after the service, and even steered me toward the portrait of Saint Nino in the back of his cathedral as the place for our picture. When I sat in Thoma’s little apartment and asked those gathered what had drawn them into the community, I didn’t hear anyone speak of LGTBQ+ issues, or the way in which our church understands the authority of scripture, or the significance of the creeds, or the number of sacraments. Instead, I heard again and again stories of what they had observed about how people in this community cared for each other, looked after each other, prayed with and for each other—how they loved each other. They had found in this gathering of believers a narrowing of the gap between proclamation and practice, and that made them want to learn more. I’m keeping that in mind as I travel from our small community in Tblisi to the extravaganza of General Convention. I have already tired of the endless complaints about what this gathering is not, or how it isn’t what it has been before—an attitude that seems almost tragically disinterested in what it might be. But I hope that notion of a Christian community marked by how its members treat each other—and the reality that it, more than anything else, builds churches—might be at least as much on display there as it is, thanks be to God, in Saint Nino’s. See you in church,  The Rt. Rev. Mark D. W. Edington Bishop in Charge The Convocation of Episcopal Churches in Europe |

Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed